In Columbus it is past time to place a historic marker at a known site that I have written about in the past and whose history has been documented by the late Sam Kaye, Carolyn Kaye, Gary Lancaster and myself.

It is the site of the first bridge over the Tombigbee River, which was built by Black bridge builder Horace King in 1842. King built at least four bridges in Lowndes County. They were over the Tombigbee River, Yellow Creek, the Luxapalila and Catalpa Creek on the Columbus-Starkville Road. Amazingly the Yellow Creek and Luxapalila Creek bridges, though wooden, remained in use into the late 1930s.

Horace King is a fascinating story, and this year marks the 180th anniversary of the commencement of construction of King’s Tombigbee bridge at Columbus. At the time he built the Columbus bridge he was enslaved but was later emancipated. After his emancipation he continued to build bridges, becoming one of, if not the most noted bridge builders in the South. The importance of King and his story cry out for a historic marker at the site of his Columbus bridge.

Though construction of the Columbus bridge began in 1842, it was not completed until 1844. It was designed and its construction was directed by King, an enslaved person owned by Alabama and Georgia bridge builder John Goodwin. In spite of his enslavement, King was usually referred to as an architect, engineer or bridge builder. The Columbus bridge was the project of Tuscaloosa businessman Robert Jemison.

It was because of Robert Jemison, a Tuscaloosa resident with business interests in Columbus, that King came to Columbus. Jemison had purchased land around Tuscaloosa, Columbus and Pickensville, Alabama, and his nephew Green T. Hill operated his stage line out of Columbus.

Jemison also developed large grist mill and sawmill complexes at Steens on the Luxapalila near Columbus, at Tuscaloosa and at Pickensville. His Steens mill was a three-story brick building with grinding stones for both corn and wheat. By the mid-1840s the mill could produce 4,000 barrels of flour a year. The sawmill could cut up to 2,500 board feet a day.

Unheard of in the antebellum South, King, while a slave, rode unsupervised inside stagecoaches with the white passengers. He at other times, while enslaved, was the sole supervisor of other slaves, including transporting them across state lines. Those actions were contrary to law and custom. During the construction of the Columbus bridge, King worked as project supervisor, even hiring and supervising white workers. Records also reflect King was paid wages of about $4 a day at a time when white carpenters were only paid about $2 and white master carpenters about $3. King’s association in business with Goodwin and Jemison and his reputation as a bridge builder gave him freedom of action and movement not normally allowed for other enslaved persons.

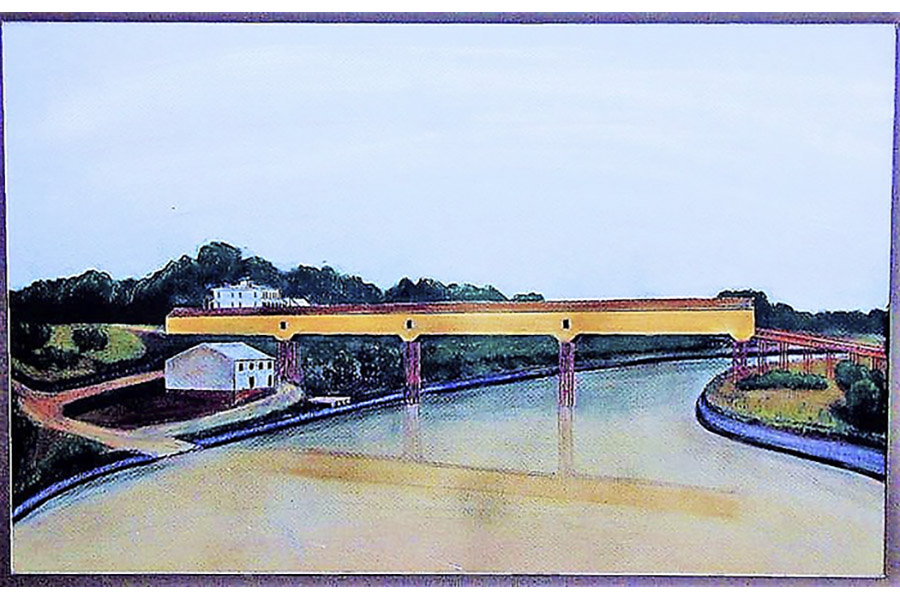

The only surviving description of the Columbus bridge, which crossed the river at the west end of Fourth Avenue South, is contained in an 1845 letter from Jemison written after the bridge was completed but before all expenses had been paid: “The length of the Bridge at Columbus (exclusive of Land Bridge of which there is about 160 to 175 ft.) is 420 ft. The height between floor & roof beams is I think 18 ft. Width inside of trusses 22 ft. from out to out 24 ft. These dimensions are given from recollection but do not materially vary from the true dimensions. It is built on four wooden piers or rather two piers & two abutments. The two piers are about 60 ft. in height, one of the abutments 40 to 50 & the other not more than 20 to 25 … cost of the bridge, it will not be less than fifteen nor more than eighteen thousand dollars.”

Goodwin turned down the then princely sum of $15,000 in an offer to purchase King and instead with Jemison petitioned the Alabama Legislature that King be emancipated. The petition requested that the emancipation be in a manner that did not place on him the many restrictions placed on free Blacks in Alabama at the time. He was emancipated by legislative act on Feb. 3, 1846. After receiving his freedom, he entered into a partnership with Goodwin and continued working with Jemison. Goodwin died in 1859, and King purchased an expensive marble monument for him inscribed with Goodwin’s name, birth and death dates and “This stone was placed here by Horace King, in lasting remembrance of the love and gratitude he felt for his lost friend and former master.”

During the Civil War King did contract work for the Confederate government including assisting in the construction of Confederate gunboats. His sons worked with him, and it was probably a move by King to keep his sons from being drafted into the Confederate army. Free Blacks could be drafted into Confederate military service, not in combat roles but in support services such as teamsters or carpenters. However, the troubles of war did not pass him by for his home was looted by General Sherman’s troops during their march through Georgia. After the war King and his sons resumed building bridges across the South and maintained their reputation as the region’s best bridge builders.

An excellent book on Horace King is “Bridging Deep South Rivers” by John Lupold and Thomas French, University of Georgia Press.

Recently I’ve been researching the route of the Choctaw Trail of Tears through the Starkville area. Not many people realize that a branch of the Choctaw Trail of Tears passed through the edge of Starkville as an 1832 road named the Indian Immigration Road. With the founding of Starkville, the road seems to have disappeared from history. Once its route through present-day Starkville is pinpointed a historic marker telling its sad story should be erected but that is the subject of a future column.

Rufus Ward is a local historian.

Rufus Ward is a Columbus native a local historian. E-mail your questions about local history to Rufus at [email protected].

You can help your community

Quality, in-depth journalism is essential to a healthy community. The Dispatch brings you the most complete reporting and insightful commentary in the Golden Triangle, but we need your help to continue our efforts. In the past week, our reporters have posted 46 articles to cdispatch.com. Please consider subscribing to our website for only $2.30 per week to help support local journalism and our community.